Yale won’t fully offset Trump’s tax through endowment spending. Why?

Amay Tewari

Despite having a multibillion-dollar endowment, Yale is enduring budget cuts and financial tightening this year in response to President Donald Trump’s recent endowment tax hike.

The tax-and-spending bill that Trump signed in July adjusted the annual tax on universities’ endowment revenues from the constant 1.4 percent tax established in 2017 to a tiered tax with a maximum tax rate of 8 percent. Based on the size of its endowment, Yale falls under the 8 percent tax rate. The tax will begin affecting Yale’s endowment returns on July 1, 2026.

Yale’s endowment sits at around $41 billion, the largest university endowment in the United States other than Harvard’s. The University is second to Princeton in university endowment per student at over $2 million.

Administrators have estimated that the endowment tax will roughly cost Yale an additional $300 million per year. But three tenets of Yale’s endowment stewardship strategy make it improbable that the University would be able to immediately increase the funds the endowment could contribute to the University’s operating budget.

Instead, the new endowment tax will require the University’s budget to adapt “if Endowment spending is to remain sustainable,” Yale Investments Office spokesperson Marcella Rooney wrote to the News.

Low liquidity, higher returns with the Yale Model

In 1985, Yale professor and Nobel laureate James Tobin, who influenced the University’s investment strategy, suggested an unexpected candidate to manage Yale’s Endowment: a young former mentee of his named David Swensen. Swensen went on to develop what is now called “The Yale Model,” the prevailing investment philosophy of top endowments today.

The Yale Model, also known as the Swensen Model or the Endowment Model, is an investment strategy that encourages investors to take on significant financial risk and leave money invested in the market for long periods of time.

Historically, endowment funds are invested in five to eight different asset classes at any given time, depending on how the asset classes — different types of investments, such as stocks, bonds, real estate and private equity — are defined, according to Alex Hetherington ’06, a managing director at the Yale Investments Office. The Yale Model heavily diversifies investments and encourages investors to avoid asset classes with low expected returns, Hetherington said.

Swensen’s investment philosophy, which has been widely adopted by other universities for their endowments, centers around the idea that liquidity — how easy it is to turn an investment into cash — should be avoided, not desired.

According to the investments office, the Yale Model is characterized by heavy investment in less liquid asset classes such as private equity — a financial market that allows large stakeholders to buy controlling stake in private companies, make them more profitable and sell them at higher prices — and less investment in liquid assets, like shares in the stock market, which are usually considered to be low-risk and low-reward.

Because a university of Yale’s size is well-positioned to take on significant financial risk, Yale’s investment strategy has added over $30 billion in value to the endowment over a 30-year period, which demonstrates, according to a video on a Yale webpage, that the Yale Model is more lucrative than an investment strategy that would leave Yale’s endowment in low-risk investments for long periods of time.

The advantage of a high-risk, low-liquidity investment strategy that tends to leave money in the market for long periods is that investors avoid the costs associated with moving money in and out of the market in response to market changes.

But the approach comes with a clear disadvantage: a less liquid portfolio means cash is a lot harder to access at any given moment. The endowment can’t move large amounts of money around the market easily, even in times of political pressure, financial crisis and uncertainty, such as Trump’s endowment tax hike.

“You want to figure out how much risk you want to take, and then you want to allocate your portfolio, and then don’t fool around every time you see something happening in the economy,” Andrew Metrick ’89 said. Metrick, a School of Management finance professor, was an undergraduate research assistant to Tobin and later a close colleague of Swensen’s.

“There are rewards for people who are willing to stay put and wait out the bad times,” Metrick said.

Kelly Shue, also a finance professor at the School of Management, echoed Metrick. The downside of an illiquid strategy comes to the fore under economic stress, she said.

“What we are learning in the current climate is that many universities do want liquidity right now, it turns out, and in many cases they wish they had more liquid investments,” Shue said.

The smoothing formula

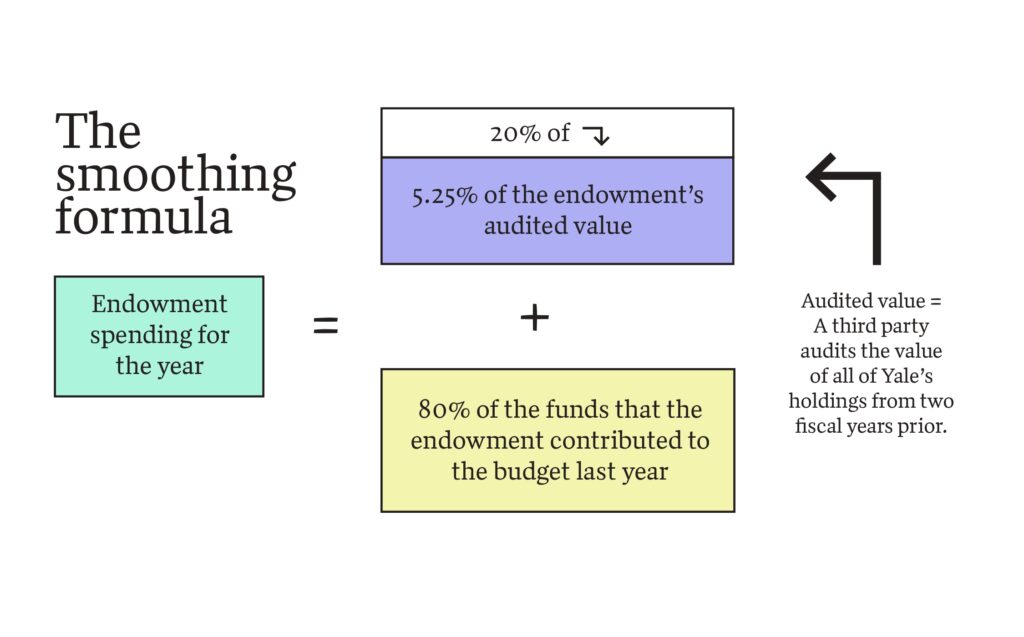

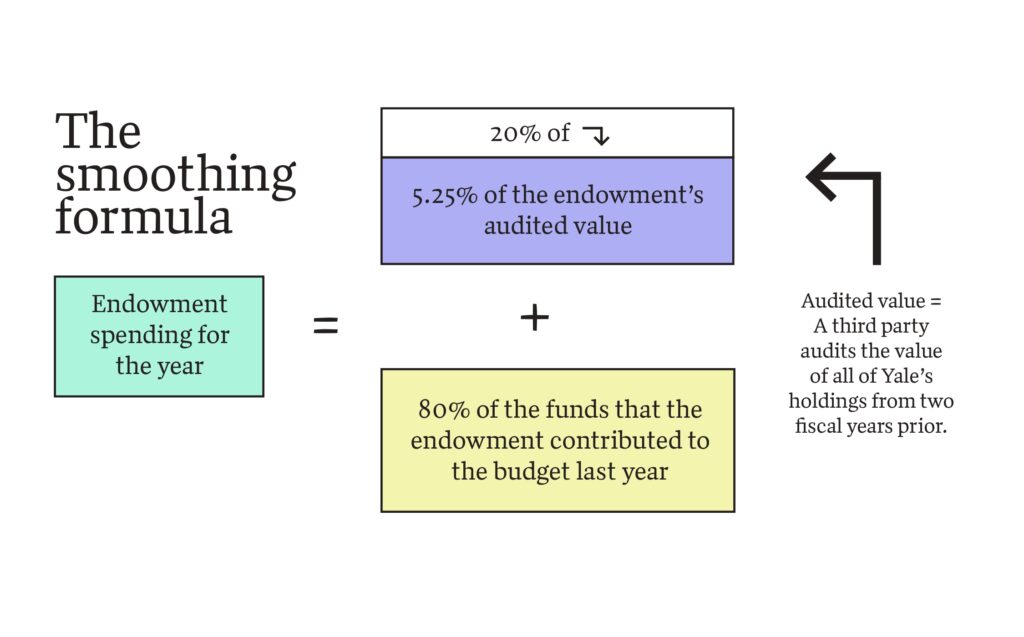

Yale’s endowment managers use what’s called a smoothing formula to calculate how much of the endowment they will contribute to the University’s operating budget in a given year.

In order to grow from year to year, the endowment must appreciate at a rate that outpaces inflation rates.

Instead of spending endowment funds based on financial needs, Yale spends a carefully calculated percentage of the endowment’s revenue. Every year, Yale aims to spend 5.25 percent of its endowment value. Higher education inflation — measured on its own index, separate from consumer inflation — occurs at a rate of roughly 4 percent each year as noted on Yale’s webpage explaining the endowment.

Therefore, the endowment must grow by 9.25 percent per year, through investment returns and new donations, in order to maintain its real value while also providing essential funds to the university at a relatively constant rate, the webpage notes.

The smoothing formula helps Yale ensure that its endowment spending rate — the amount it can contribute to the budget — is less reactive to market fluctuations. The formula slows the incorporation of those fluctuations into Yale’s budget.

Each year, Yale uses the smoothing formula to ensure endowment spending roughly meets the target spending rate of 5.25 percent.

When Yale’s endowment experienced a negative 25 percent return in 2009 because of the Great Recession, that loss in value was incorporated into endowment spending over the course of the next two years and beyond, allowing endowment spending to fluctuate far less than it would have under an annual calculation.

The reactivity of endowment spending to market conditions is minimal by design, aiming to provide “predictable, sustainable funding for university operations, regardless of market volatility,” Rooney wrote.

According to Hetherington, the money the endowment provides for the University’s budget each year comes from a variety of sources. The investments office plans in advance to make sure it has the liquidity available to hand over to the university.

The investments office is only one of the parties that controls how the endowment is funded and how its revenue is disbursed. The investments office invests endowment funds, but donors supply those funds, and the Yale Corporation, in response to recommendations from administrators and experts, sets the formulas that the University uses to calculate what funds they use and when, Hetherington said.

“We have a diversified and resilient investment strategy that has enabled us to grow the Endowment in a variety of economic climates,” Rooney wrote. “Unfortunately, though, we do not expect to be able to mitigate the full financial impact of the tax increase.”

Investing in the interest of future generations

In 1974, Tobin defined what is now called intergenerational equity — the idea that institutions and individuals owe fiscal responsibility and growth to future generations.

While many individuals and businesses invest so that they or their direct descendants can benefit from returns, Yale invests its endowment in the interest of Yale generations far in the future, Rooney wrote in an email. Because of this, Rooney wrote, the endowment cannot function as an unlimited pool of money for the University to draw from in times of economic uncertainty.

“While Yale Investments manages the endowment funds as a single pool to ensure that future generations benefit from the same excellent resources available today, the University cannot dip into that pool as if it were a piggy bank available for any worthy expenditure,” Rooney wrote.

The Hall of Graduate Studies, the central tower of the Humanities Quadrangle, is named Swensen Tower in honor of Yale’s longtime Chief Investment Officer.

link